July 23, 1984

THE WAITING IS OVER AFTER SIX YEARS OF RUGGED TRAINING, THE U.S. WOMEN'S VOLLEYBALL TEAM IS STILL INTACT—AND LOOKING GOLDEN

JOAN ACKERMANN

THE WAITING IS OVER AFTER SIX YEARS OF RUGGED TRAINING, THE U.S. WOMEN'S VOLLEYBALL TEAM IS STILL INTACT—AND LOOKING GOLDEN

JOAN ACKERMANN

"Whoop! Aaaa-ai!" Arie Selinger, coach of the U.S. women's national volleyball team, which will transform itself virtually intact into the Olympic team, has just smashed an overhand ball toward the knees of 6'5" Flo Hyman, who drops to the gym floor like a folding lawn chair. Meeting the ball, her joined forearms give slightly, absorbing a force that would flatten a small animal. The ball, spent and seemingly weightless, drifts toward the ceiling.

"Hup! Ha!" Selinger grunts. He tosses another ball just out of Hyman's reach, and her extended body stretches sideways in midair, telescoping out a few more inches. She misses the ball and collides with the floor. "Hup! Aaa-ah!" Scrambling, she veers over, twists and dives for another one, reaching, just barely touching it with the knuckles of her clenched right fist. The ball angles off toward the back wall like the ejected shell of a fired bullet. Selinger pushes the next shot gently out of his upturned palm as if his hand were exhaling a huge soap bubble. Hyman lunges and pops it up. Somersaulting forward, she's on her feet for another ball, ignoring the one that hits her smack on the shoulder.

Hyman, 29, a phenomenal athlete who seemingly strikes the ball with enough ferocity to rearrange the grain in a wood floor, and Selinger, 47, a former Israeli commando, are old friends. They've been at this for nine years, working on her defensive skills, dispelling her fear of falling from her own great height, venturing across new thresholds of pain. They and the 12 other women on the team have spliced their wills to pursue two common goals: promoting their sport and winning an Olympic medal, preferably a gold one.

On the far side of the net, other exceedingly fit, long-limbed women with taped fingers and bruised thighs practice a different drill. Their sneakers chirp on the floor like bantering parakeets; in a higher octave are the shrill squeaks of skin screeching across the floor as player after player dives headlong for just-out-of-reach balls and then slides 10 feet into a forward somersault. "Go, Kim!" says a teammate. "You can do it, Jeanne." "Atta way, Linda," chimes in another hoarse voice. "Nice, Julie. Nice." Cheers of encouragement, pained cries and exclamations from physical exertion swell in the air as white balls rise and fall like exploded corn in a popping machine.

Selinger fires another ball at Hyman. His arm is so tired he can't feel it. "What do you mean does it hurt? It's dead," he'll say later. After 20 balls, Hyman is panting, her shoulders rolled forward, her long arms dangling, her third jersey of the practice soaked through with sweat. Her eyes show no sign of defeat, but when the next ball comes, her head just rolls back over her shoulder as she watches it land on the back line. "Again, again, again," says Selinger, tossing up yet another one. "Well, give it to me," says Hyman, swaying back and forth before she heaves her tired body through three seconds of flying time out of what is just another of her nine-to-five workdays.

The women's national volleyball team is the first one in an Olympic sport in the U.S. to live and train together year-round. Since 1978 the players have studied and practiced volleyball with a dedication that would have made them doctors by now if they'd been in med school. It's an intense, driven group with a gritty instinct for survival infused by its intense, driven coach, a man whose gaze is so penetrating that a customs and immigration official at the Moscow airport was forced to look away from him during a routine stare-down. "He couldn't take it; first he broke, then he smiled," says Selinger, who spent three years of his early childhood in a concentration camp, daily subjected to far worse visions than that of a menacing Soviet official.

Many of the women, all in their 20s, have been playing volleyball for 10 years; between them they have done enough spiking to lay a railroad track across the U.S. None is married, none has finished college, and some will have lost their scholarships by the time they return to school. All have traded normal lives to be the best in the world at what they most love to do: play volleyball. Not beach volleyball—power volleyball, the exhilarating fast-paced game that the Soviets and the Japanese play.

That an amateur team has worked so hard so long without hope of financial compensation is baffling to a public accustomed to reading about six-figure salaries for athletes. The team's '83-84 training program—eight hours a day, six days a week, with a couple of weeks off for vacation around Christmas—is more rigorous than any pro team's. Such dedication has made it a provocative presence in American sports. Some observers find it unpalatable that women train so hard, and others find the rigors of the program ill-suited to the U.S. ethos.

"The fact that the women work so hard is difficult for people in this country to understand," says Marlon Sano, an assistant coach. "They just can't relate to it. The apex of sports here is pro sports. These women are pioneers."

"The rewards aren't monetary," says team captain Sue Woodstra, 27, of Colton, Calif., who looks forward to getting a dog, not a contract, after the Olympics, "and a lot of people don't understand it."

But the result of such single-minded-ness is that the U.S. team is one of the world's best, ranking in the top three with China and Japan. Regardless of how the team fares at the Olympics, it has already done remarkable things.

"It's the biggest success story I've seen in a long time," says Vic Braden, the tennis pro who's an avid supporter of the team. "Coming from nothing to being so highly ranked. So few people really understand what they've done."

Ten years ago, women's world-class volleyball was as much a part of the American scene as cricket or ostrich racing. Then in 1975, the board of directors of the U.S. Volleyball Association decided to create a full-time program, realizing that the only way America would ever become competitive would be to duplicate the demanding programs in other countries, specifically Japan.

A national team was created and based in Pasadena, Texas, and Selinger was hired as its full-time coach. He had guided the Israeli women's team and was just finishing up his doctorate in the physiology of exercise at the University of Illinois. In 1978, Selinger merged his squad with a strong club team from Westminster, Calif. that was coached by Chuck Erbe and that included Woodstra, Carolyn Becker and Debbie Green, all of whom are on the '84 national team. The combined team then moved to Colorado Springs. In its first year, it finished fifth in the world championships and in other matches stunningly thrashed such powers as the Soviet Union, China, South Korea and Japan.

Inspired by the Japanese women's coach, Shigeo Yamada, a poet and philosopher who believes in immersing his team in the game, Selinger has insisted that his players' sole focus be the game—breathing, thinking, being volleyball. "The reason we have to train like this is because our competition does it," says Selinger over and over. "Otherwise we'd never win."

Though his hard-driving ways may have caused some fine players to leave the program, his team stands behind him.

"Arie got us all together and convinced us that this is what we need to be doing," says Laurie Flachmeier, 27, an exceptional blocker from Garland, Texas. "He told us, 'It's going to take all your time and all your dedication.' He's very persistent. When he wants something done, he doesn't stop till it's done. Correctly. Some people say he's obsessed, but you need to have that kind of devotion to succeed."

The U.S. team, whose style combines the quickness and agility of the Asians with the height and power of the Europeans, has won more than 90% of its matches in the past two years. In 1982 the U.S. won a bronze medal in the world championships and in '83 won six gold medals at world-class events, including the Varna Cup, in which it defeated the world-champion Chinese.

"America is very strong," says Zhang Yipei, the coach of the Chinese team. "It is a possibility to win the gold medal in the Olympics. Good both defense and offense."

The Chinese will provide the toughest competition for the U.S. at the Games. Their style, featuring a precise uniformity of play that fairly hums, is similar to that of the Japanese. Both teams are especially adept at defense, at unremittingly returning balls that seem destined to touch the ground. Getting a ball past the 12 hands of the Japanese team is like trying to throw a bread ball through a flock of hungry sea gulls. The Chinese, because they are slightly taller, have a stronger attack than the Japanese. But the Americans—with Rose Magers, Paula Weishoff, Rita Crockett and Hyman—have the strongest attack. Selinger says there are seven players on a team: the six players and the team itself. If that seventh American player is in good health, and provides cohesiveness and spark, the U.S. could win a gold medal.

"We feel the American team has the best chance for the gold," says the Soviet coach, Vladimir Leonidovitch Patkin. "There is a Russian saying that at home the native walls help us. If the Americans are in their best form they will win."

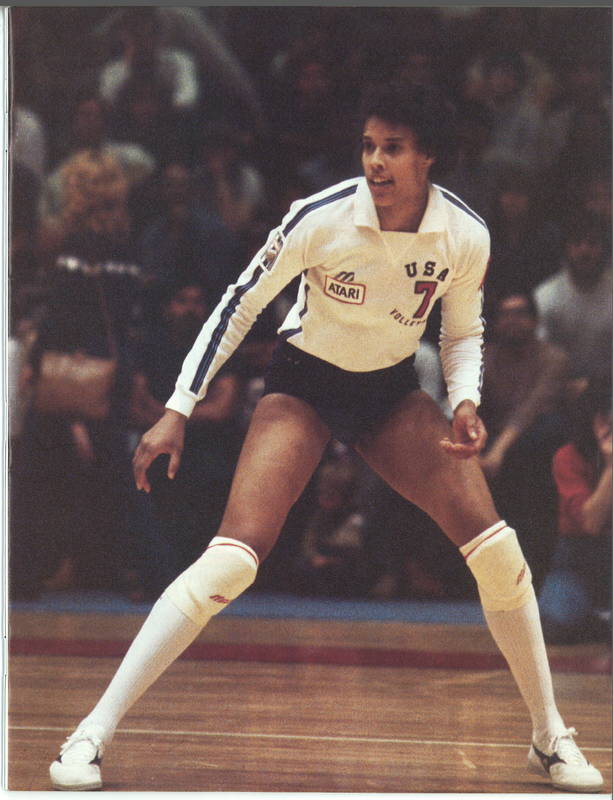

Responding to frenzied cheers of "Go U.S.A.!" from a normally restrained Soviet crowd, the U.S. team was in its best form in Riga, Latvia in May when it rallied in the fifth game of a match against the Soviet women's team to shut it out 15-0. "We were like animals let out of a cage," says Crockett, 27, of San Antonio, whose long femur bones hoist her 40 inches off the ground. With spikes strong enough to send the caviar rolling off the stale slices of bread in the refreshment stands, the U.S. team engraved a foreword to the L.A. Olympics: As far as women's volleyball is concerned, the Soviets may as well stay home.

"This match definitely eliminates any question mark in the Olympics," says Selinger. "If we take first, second or third this summer, everyone will know we really deserve it."

"The teams that need to be there will be there," says Hyman resolutely, determined not to feel the burn of yet another boycott.

For most of the U.S. Olympic athletes, news of the 1980 Olympic boycott had left them impotent, raging, stranded in a wreckage of dreams. For the women's volleyball team, whose members had lived together and trained for two years, the frustration was so acute that seven players and Selinger, more than half the team, agreed to persevere for another four years to achieve their goal. For them, the sacrifices they would have to continue making paled beside the sacrifice of abandoning their dream.

"There's no way we'd have stayed together without Arie," says the 5'4" Green, 26, of Westminster, who is one of the world's shortest and best setters. "He always fights for us. He wants the best for us. He's hard, but he lets you know when you've done well."

"If Arie hadn't stayed after the boycott, I wouldn't have stayed," says Hyman. "I didn't think anybody else could do the job. Not too many coaches have his ability to really care for their players. You have to mature them; you have to teach them. How can you find the right formula for a team if you don't know the players? Coaching is an art. The better you are, the better you produce. This team is a reflection of Arie's art."

"The team is a mirror image of the coach's personality," says Selinger. His is at once smooth and rough, charming and rude, reserved and aggressive. Refusing to sweet-talk anyone, even if it sometimes seems in the best interest of the team or the sport, he can be surly to coaches, to the press, to officials, to anyone he feels is using him.

His striking face, with high cheekbones and sharply chiseled features often cast in a stoic expression, can be unwittingly intimidating. "Ah, his face," says Green. "At first some people think it's mean. It's amazing how people you think would never be afraid of anyone can be afraid of Arie." His good looks once prompted a Twentieth Century Fox executive to send him an invitation for a screen test when he saw a picture of him in a paratrooper's uniform on the cover of an Israeli military magazine.

Selinger, who has his share of critics, feels that resentment toward him springs somewhat from the fact that he's foreign-born, although he became a U.S. citizen in 1979. "I don't think there's any doubt of that," says Braden, "but Arie is more of an American than anybody. Arie is everything this country stands for."

When Selinger was a child in Bergen-Belsen, where for three years he daily watched prisoners being beaten, his mother tried to boost his spirits by telling him of the U.S. "My mother never stopped talking about going to America," he says. "She would tell me, 'Your dad is in Israel. When we meet him, we will all go to America together, to the new land.' Always I heard my mother talking, 'America, America, America.' "

Selinger was born into a wealthy, musical family in Crakow, Poland in 1937. As a child he played the mandolin. Today, making gestures worthy of an orchestra conductor, he speaks of volleyball in musical terms: "Rhythm is the most important characteristic of the game. The inner pace has to flow. The cue is the ball, and the team has to flow with its speed." His father, Chaim, was a construction engineer who remodeled a large theater as a home for the family before the Germans came and took it over. In 1942, the Selingers were seized and separated; Arie, age 5, and his mother, Lina, were sent to Bergen-Belsen.

When Selinger was eight, he and his mother were put on a death train. "We didn't know where we were going," he says in his low, mesmerizing voice. "All of a sudden the train stopped and the engine was sent back. In the evening we could see the lightning from gunfire and hear the cannons. We knew we were very near the front.

"Early in the morning we woke up before the others. My mother used to have a sixth sense about what was going to happen, and she snuck me down from the train. The track was in a valley and at the bottom was a marsh. We went down and sat in the water, hiding, our heads sticking up, plants and stuff like that around us. At sunrise, we saw the Germans line everybody up, getting ready to execute them. Suddenly, up on the slope behind the train, we noticed all the trees were falling down. It was the American troops coming in tanks. Immediately the Germans surrendered."

Though his mother stayed behind to search for relatives, Selinger was sent to Israel, under arrangements made by the American Red Cross. Upon arriving there he was told by an aunt that his father had died in Auschwitz. Selinger lived in Ein Hamifratz kibbutz, where he excelled in track and field and was introduced to volleyball. For many years he played on the national squad and in 1965 was named coach of the Israeli women's team. In '69 he came to the U.S. with his wife, Aia, and daughter, Ayelet, to study at the University of Chicago. He went on to earn his master's degree and doctorate at Champaign, doing his dissertation on body composition.

A volleyball team has its own body composition. Selinger's fascination with seeing how things work extends into designing a team whose six bodies whir through space like the parts of a well-oiled machine. He constantly draws diagrams of game plays on scraps of paper.

"This game is so complex," he says, "it never fails to intrigue me; it's a game of geometry. I tell you I learn something new every day. In men's volleyball it's just boom, boom, boom. Power. The women have to win by skill and by outsmarting their opponent; it requires more finesse, more sophistication."

"There's so much grace in volleyball," says Aia, the team's technical adviser, who was a gymnast on the Israeli national team from 1959 to 1962. "The game is very artistic, requiring everything. You have to be quick; you fly up and come down and roll like a cat."

"It's such a joy," says Green, "so much fun, even after 11 years. When we do a good play, it feels like we're doing it for the first time." As she readies herself for the set, her fingers delicately upturned like a ballet dancer's, she does look as if she's being seized by the rush of the game for the first time. She gives the customary high fives after big points with inspired oomph.

"When everybody works together, that's what excites me," says Woodstra, a 5'9" hitter whose forearms have been pounded hairless by volleyballs. Considered the best all-around U.S. player, she seems jointless, able to curve every muscle and cell behind the ball as she moves into it.

"When it all works well, it feels like heaven," says Hyman, smiling. "That's the best way I can describe it. You feel like you're playing a song."

"Gee, did they all stay up late at a party last night or something?" a woman innocently asks, staring around the cabin of the DC-10 in which the Chinese and the U.S. players are dramatically unconscious, their bodies awkwardly folded as if they had been hastily stashed away—heads flopped forward on tray tables, legs sticking out into the aisles, big feet up on the walls, elbows jutting out, mouths wide open. Six exhibition matches in 10 days will be played on this particular tour in April, in Long Beach, Miami, Dallas, Minneapolis, Portland and San Francisco. Now, among the sleeping players there are undoubtedly enough dreaming of volleyball to get up an in-flight game.

Stewardesses should caution passengers who sit next to volleyball players. They kick, twitch, thrash, hit, block, lunge and spike balls in their sleep. "I was sitting in the middle between two people," recalls Woodstra, with some embarrassment, "and I swung my arms out and hit them both."

In perhaps the most spectacular defensive play of her career, Hyman once broke her watch crystal. "I was dreaming we were getting 21 balls [as the athletes call a hitting drill] and there was one coming straight at me, vrooom, like a line drive. I deflected and hit the armrest. When we arrived in Japan I looked at my watch to change the hour and saw then that it was smashed." She grins. "It dawned on me how it got that way."

"I had a dream last night that a ball was coming at me," says Ruth Becker, the team manager from Norwalk, Calif., who has been with the squad for six years, including a two-year leave of absence, "and I must have jumped six inches in the air." Once, during a practice in which she failed to jump a few inches out of the way, a ball struck her side with such force that a week later her appendix burst. (She has seen only one ball burst.) Becker is called Ma by everyone, including her daughter Carolyn, 25, who has a devastating serve. Ma shags balls at practice, washes uniforms on the road, calms frayed nerves, does stats during games and buys Easter eggs for the team.

Now she's in a seafood restaurant in Miami, sitting next to her husband, Paul, who occasionally assists the team. The Chinese are checking out a Chinese restaurant in another part of Miami. Across from Ma, Weishoff, a superb hitter, is making lemonade, not by spiking the lemons on the table but by painstakingly squeezing them into her ice water. From the other end of the table a few after-dinner mints come flying through the air, accompanied by raucous laughter. Outside, by the front door, a couple of players feed crackers to carp in a lighted pool. Selinger sits next to Green, who's struggling with her lobster. Smoking a cigarette, he studiously observes her efforts to excavate the meat.

"That's a lot of work for a little meat," he says after a while, amicably placing his hand on her shoulder.

She perseveres. He, of all people, should know that when the meat is that sweet, it's well worth the struggle.