Through her death, Hyman helps Austin and others to live

By Randy Harvey

June 28, 2014

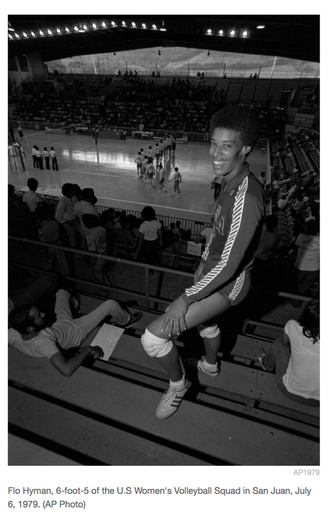

AP1979

Flo Hyman, 6-foot-5 of the U.S Women's Volleyball Squad in San Juan, July 6, 1979. (AP Photo)

Flo Hyman's sister vividly recalls almost three decades later the dream. She woke up and immediately called her sister despite the time difference in Japan, where Hyman played professional volleyball.

"I told Florie, 'I have a feeling something bad is going to happen to you,' " Barbara Bedford said last week from her home in Phoenix.

"I told her, 'I saw you die. You leaned over in your coach's lap and said, 'Go team.' And then you died.' "

Six months later, while on the bench cheering for her team in the Japan Volleyball League, Hyman suddenly slid to the floor and died. She was 31, less than two years removed from leading the United States to a silver medal in the 1984 Summer Olympics.

Bedford tried to persuade her sister to see a doctor.

"I knew she wouldn't do it," she said. "I think she knew something was wrong with her and a doctor would tell her to quit playing volleyball. She wouldn't have done that. She loved it too much."

Hyman, the University of Houston's first woman scholarship athlete, didn't take necessary precautions to save her life. But, in death, she has saved others.

That started with her brother, Michael. After an autopsy revealed Hyman suffered from Marfan syndrome, a rare genetic disorder that weakens the body's connective tissue, other family members were tested. Michael was not diagnosed with Marfan but with an enlarged aorta that might have gone undetected. He is alive today, his sister said, because of the resulting open-heart surgery.

Most recently, former Baylor basketball player Isaiah Austin was diagnosed with Marfan, ending his career four days before he would have been drafted Thursday night by an NBA team.

Matthew Minard

Athletics – Men’s Basketball (MBK, MBB) – Marketing poster - practice facility at Ferrell Center – 09/18/2013

Although Hyman died more than 28 years ago, Dr. Jonathan Drezner, team physician for the University of Washington and Seattle Seahawks football teams and an expert in sudden cardiac arrest among athletes, said Austin and others owe her a debt of gratitude.

"To make that connection between Isaiah Austin and Flo Hyman is entirely logical," he said. "Her death serves as a constant reminder for us to be on the lookout for conditions that might cause aortic rupture."

Drezner said awareness among the National Association of Athletic Trainers and the American Medical Society for Sports Medicine has increased dramatically since Hyman's death.

The Marfan Foundation has worked with Congress and the National Institutes of Health to assure the disease is not overlooked by doctors at a grass-roots levels.

"Flo literally was a game-changer," said Carolyn Levering, Marfan Foundation president. "Even today, when we have conversations with people, they talk about her."

Hyman showed physical signs of Marfan - extraordinary height, near-sightedness, long arms and large hands - in elementary school, when she grew as tall as her father. The family doctor recommended a specialist. Bedford said Hyman was tested often for heart conditions but not Marfan because the disease was considered so rare.

Hyman, who was 6-5, left home in Inglewood, Calif., in her late teens to join a club volleyball team in Pasadena, Texas, which later became home to the national team, and remained in Houston to train with the U.S. while playing for the Cougars.

"She was the world's best volleyball player and the most humble athlete I've ever met,'' said Ruth Nelson, who played with Hyman on the national team and coached her at UH.

"I remember when we traveled in Japan in '74," Nelson said. "Everyone wanted to take pictures of her feet because they were so large. But she wasn't sensitive. She was so kind, the last one everywhere signing autographs."

Nelson coaches youth volleyball players in Dallas. When one began to resemble Hyman in structure, Nelson advised the child's mother to take her to a specialist who would test for Marfan.

"I never would have thought of that without Flo," Nelson said.

Austin was diagnosed after a routine NBA predraft physical revealed enlarged arteries in his heart.

NBA commissioner Adam Silver invited Austin to the draft in Brooklyn, N.Y., bringing him to the podium for an emotional introduction.

In the audience were members of the Marfan Foundation, serving as a support group for Austin and his family.

Austin told them he wants to become a spokesman, which he reiterated to reporters when he said, "I am only 20 years old, and I am ready to do whatever I can and make my life better. I'm going to share my story with as many people as I can."

Said Levering: "Flo, unfortunately, didn't have that opportunity. But her passing has given others the chance for longer and more healthy lives."

Bedford cried when she learned of Austin's condition. She also rejoiced. A career ended abruptly, not a life.

"Amen for Flo, huh?"

By Randy Harvey

June 28, 2014

AP1979

Flo Hyman, 6-foot-5 of the U.S Women's Volleyball Squad in San Juan, July 6, 1979. (AP Photo)

Flo Hyman's sister vividly recalls almost three decades later the dream. She woke up and immediately called her sister despite the time difference in Japan, where Hyman played professional volleyball.

"I told Florie, 'I have a feeling something bad is going to happen to you,' " Barbara Bedford said last week from her home in Phoenix.

"I told her, 'I saw you die. You leaned over in your coach's lap and said, 'Go team.' And then you died.' "

Six months later, while on the bench cheering for her team in the Japan Volleyball League, Hyman suddenly slid to the floor and died. She was 31, less than two years removed from leading the United States to a silver medal in the 1984 Summer Olympics.

Bedford tried to persuade her sister to see a doctor.

"I knew she wouldn't do it," she said. "I think she knew something was wrong with her and a doctor would tell her to quit playing volleyball. She wouldn't have done that. She loved it too much."

Hyman, the University of Houston's first woman scholarship athlete, didn't take necessary precautions to save her life. But, in death, she has saved others.

That started with her brother, Michael. After an autopsy revealed Hyman suffered from Marfan syndrome, a rare genetic disorder that weakens the body's connective tissue, other family members were tested. Michael was not diagnosed with Marfan but with an enlarged aorta that might have gone undetected. He is alive today, his sister said, because of the resulting open-heart surgery.

Most recently, former Baylor basketball player Isaiah Austin was diagnosed with Marfan, ending his career four days before he would have been drafted Thursday night by an NBA team.

Matthew Minard

Athletics – Men’s Basketball (MBK, MBB) – Marketing poster - practice facility at Ferrell Center – 09/18/2013

Although Hyman died more than 28 years ago, Dr. Jonathan Drezner, team physician for the University of Washington and Seattle Seahawks football teams and an expert in sudden cardiac arrest among athletes, said Austin and others owe her a debt of gratitude.

"To make that connection between Isaiah Austin and Flo Hyman is entirely logical," he said. "Her death serves as a constant reminder for us to be on the lookout for conditions that might cause aortic rupture."

Drezner said awareness among the National Association of Athletic Trainers and the American Medical Society for Sports Medicine has increased dramatically since Hyman's death.

The Marfan Foundation has worked with Congress and the National Institutes of Health to assure the disease is not overlooked by doctors at a grass-roots levels.

"Flo literally was a game-changer," said Carolyn Levering, Marfan Foundation president. "Even today, when we have conversations with people, they talk about her."

Hyman showed physical signs of Marfan - extraordinary height, near-sightedness, long arms and large hands - in elementary school, when she grew as tall as her father. The family doctor recommended a specialist. Bedford said Hyman was tested often for heart conditions but not Marfan because the disease was considered so rare.

Hyman, who was 6-5, left home in Inglewood, Calif., in her late teens to join a club volleyball team in Pasadena, Texas, which later became home to the national team, and remained in Houston to train with the U.S. while playing for the Cougars.

"She was the world's best volleyball player and the most humble athlete I've ever met,'' said Ruth Nelson, who played with Hyman on the national team and coached her at UH.

"I remember when we traveled in Japan in '74," Nelson said. "Everyone wanted to take pictures of her feet because they were so large. But she wasn't sensitive. She was so kind, the last one everywhere signing autographs."

Nelson coaches youth volleyball players in Dallas. When one began to resemble Hyman in structure, Nelson advised the child's mother to take her to a specialist who would test for Marfan.

"I never would have thought of that without Flo," Nelson said.

Austin was diagnosed after a routine NBA predraft physical revealed enlarged arteries in his heart.

NBA commissioner Adam Silver invited Austin to the draft in Brooklyn, N.Y., bringing him to the podium for an emotional introduction.

In the audience were members of the Marfan Foundation, serving as a support group for Austin and his family.

Austin told them he wants to become a spokesman, which he reiterated to reporters when he said, "I am only 20 years old, and I am ready to do whatever I can and make my life better. I'm going to share my story with as many people as I can."

Said Levering: "Flo, unfortunately, didn't have that opportunity. But her passing has given others the chance for longer and more healthy lives."

Bedford cried when she learned of Austin's condition. She also rejoiced. A career ended abruptly, not a life.

"Amen for Flo, huh?"